SPECIAL FEATURE: Australian architect Darrel Conybeare joined the Eames office in Venice, California, in 1967, as a young graduate of the Architecture and Civic Design Masters program at the University of Pennsylvania. The next three years were beyond his greatest expectations …

The design approach at Street Furniture Australia has been influenced by the Eames office, where Darrel Conybeare (shown), SFA co-director, worked for a number of years.

I was amazed that I had won the job.

In 1967, American architect Denise Scott Brown introduced me to Ray and Charles Eames after I had moved to California. My interview took place at 901 Washington Boulevard, Venice, California, the design home of their extraordinary practice. Ray and Charles described the nature of the job, and I explained my purpose in coming to America to study with Louis Kahn and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania. At first, I thought, “If Im lucky, they’ll give me half an hour,” but I spent the whole day at the studio, as Ray and Charles showed me various films they had made [the duo produced 125 short films in 28 years] and talked extensively about their projects. Later, I was amazed that I had won the job for I knew so little about their many accomplishments beyond furniture design. Once I started work there, however, I learned fairly quickly.

Ray and Charles Eames documenting a model for Mathematica (1961), their first show.

I never expected to discover the richness that I found there.

Ray and Charles had a “learning by doing” philosophy, and, as part of their wide-ranging and innovative practice, they often used people in the office to do things that they had no experience in.

There was a modest staff of about 25 that consisted of urban designers, film makers, furniture designers, researchers, a librarian and a secretary. Charles and Ray worked very hard, arriving at 9:30 am, working all day in the studio – or “the shop”, as Ray called it – then leaving at about 11 pm.

“It was a magical place.”

From my viewpoint, their breakthroughs in furniture design had happened years earlier, but development was ongoing. There was a revisited interest in film and experiments, such as Tops (1969) and, much later, Powers of Ten (1977), and exhibitions such as Photography and the City (1968), the birth and evolution of computers – ideas that related to a celebration of the American age.

Throughout their lives, Ray and Charles collected things – photographs, objects, toys, colour samples and memorabilia – and, when space in the studio became limited, they built a warehouse to accommodate this collection. At a time when we were being taught the virtues of minimalism in Architecture, Ray and Charles clearly started the framework of another aesthetic, which said it was good to make collections of things so long as the process embraced a search for the object’s inherent ‘design integrity’. That was the discipline.

Ray and Charles created their own design world, which referred to an innate interest and excitement in nature’s forms, and their passion engrossed the whole studio. Not a day would go by that wouldn’t involve some kind of revelation about how the world works. They adhered to the concept of ‘object integrity’; they believed that somehow the process of design, beyond form and function, was to embrace delight, pure and simple.

“Ray and Charles adhered to the concept of ‘object integrity’.”

Charles, during a CBS interview in the studio, was asked, “Did all this [the interviewer waved towards the hundreds of elements that graced the walls and spaces] … did all this come in a flash?” To which the guarded answer, after a pause, was, “Yes, I suppose, a kind of flash – about a 25-year flash!”

It was a magical place.

Working on the National Aquarium Project.

The Eames’ reputation put a certain pressure on those who worked for them. I had to get used to the incredible range of work on hand, an urgent need to prioritise, the very personal way that Charles wanted to see results being achieved, the meetings with and debriefings from clients, such as IBM, Westinghouse, the Smithsonian, Herman Miller – a ‘who’s who’ of American design glitterati.

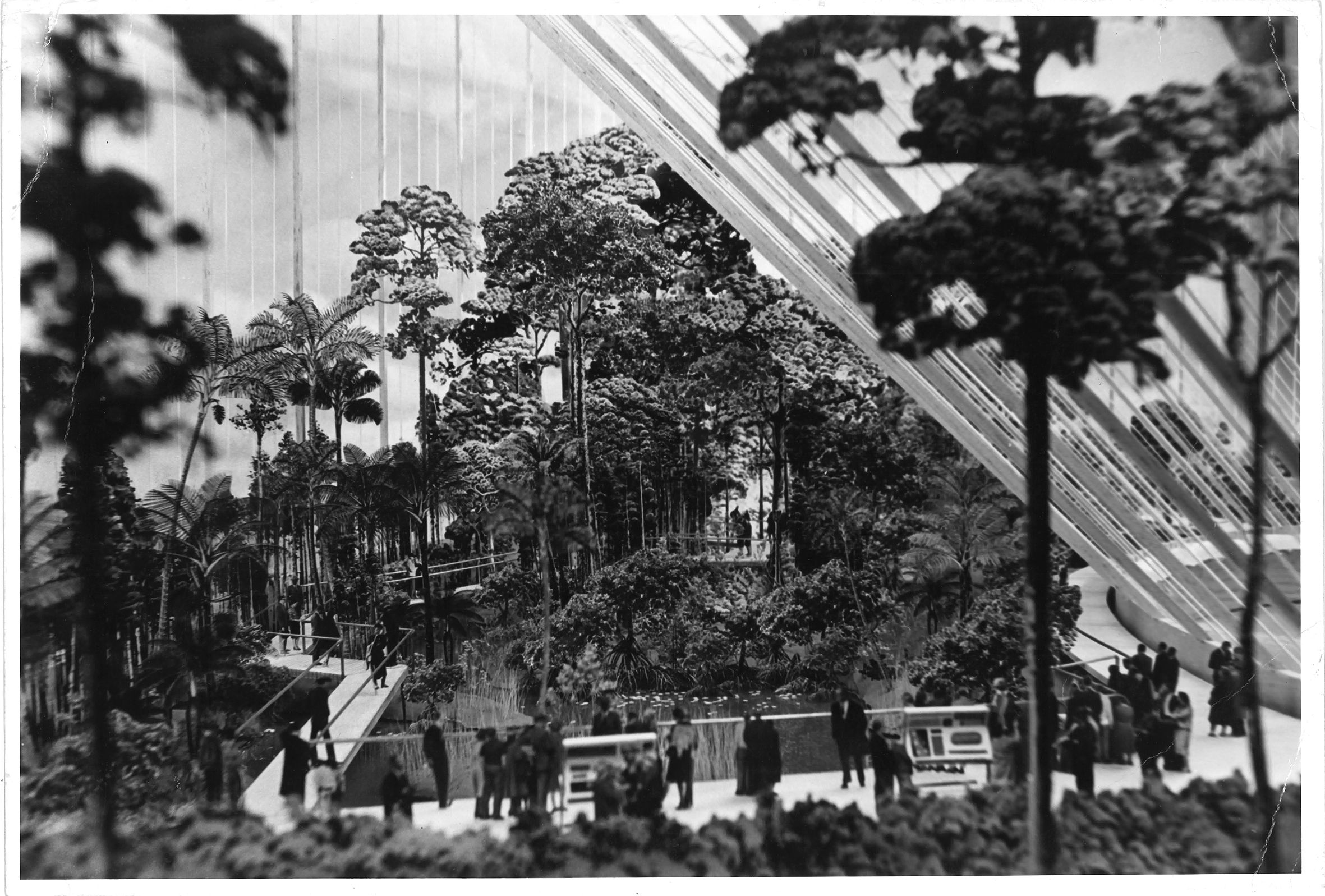

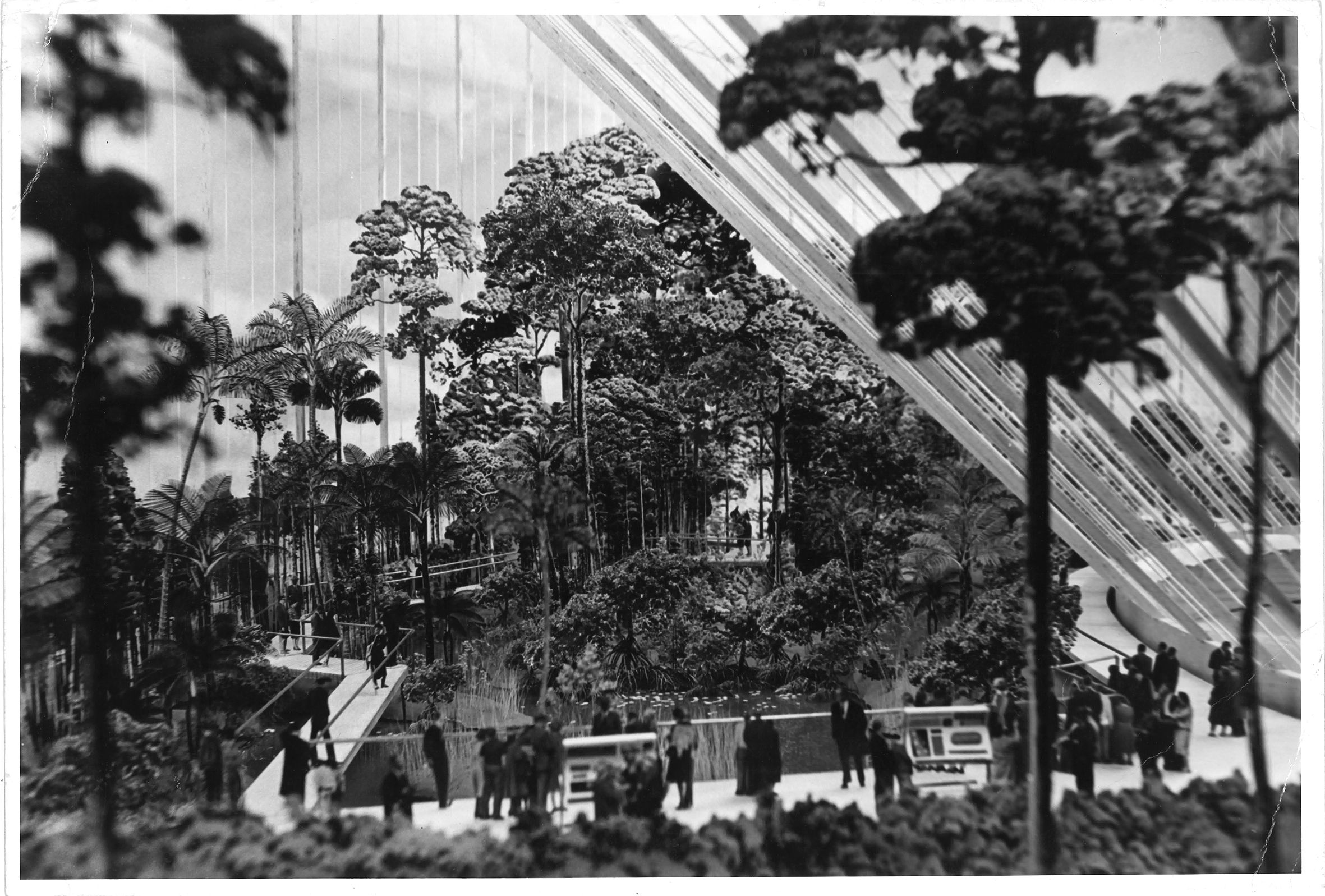

Detail of Aquarium model: view of the greenhouse housing a fragment of the Florida Everglades ecosystem.

Four to five weeks into my role, I was appointed the project design director for the National Fisheries Centre and Aquarium in Washington D.C. It involved the refinement of many component elements, including: a massive eight-metre high coral reef ecosystem; a typical North American freshwater front stream; a fragment of the Florida Everglades ecosystem, housed in a massive roof-level greenhouse; east and west coast intertidal zones, complete with wave motion, bird and animal ecosystems; a roof terrace beaver pond; and a concourse information centre.

Detail of Aquarium model: view of the trout stream.

To best understand the science of maintaining an aquarium of this scale, the Eameses set one up in the office – complete with a large variety of saltwater marine life, including an octopus (which was placed in an isolated tank). The octopus became an office mascot of sorts and, at the end of the work day, would appear to wave a tentacle goodbye to those departing. It even escaped one night – but was returned unharmed to its tank the next day.

Photograph of the octopus that took residence in the Eames office.

Following the production of the explanatory film Aquarium (1967), I was asked to produce a black-and-white brochure for use by the Department of the Interior. It described the National Aquarium building and its layout and also outlined the educational and research goals of the institution. Such detailed visual depictions of projects was characteristic of the Eames’ process, and gave the impression that a project actually existed. Ray and Charles were passionate about storytelling and creating excitement for a new idea.

The Aquarium was conceived as a 21st-century natural history museum, complete with living ecosystems. It predated, of course, the arrival of the Computer Age. Its building budget was cut short and the government commitment to continue the project became tangled with events sparked by the Washington D.C. riots in 1968. It was never to be.

What I learned from Ray and Charles Eames.

The Eames studio was the epitome of a highly successful multi-disciplinary research-based studio. The studio was driven by an extraordinary commitment to intense and continuing design refinement. This process would apply to projects past and present, and was especially notable in the recurring Eames’ furniture products manufactured by Herman Miller.

“I was overwhelmed by a sense of focus and concentration on minutiae in Ray and Charles’ practice.”

As a young architect, I was overwhelmed by a sense of focus and concentration on minutiae in Ray and Charles’ practice. Forty-five years later, I can say that the Eames experience has had an abiding influence on every aspect of my professional life in design, planning architecture and urban landscape design.

I learned how to lift the design standard to an optimum level at each stage of the design process; the importance of building prototypes at both small scale and full size for all design outputs, products and graphic elements; and, ultimately, that there is no substitute for simple hard work in tackling any design challenge.

Charles taught me that it was important to have the foresight to know what the next meaningful challenge would be, to be aware of its complexity and to know when its resolution has been discovered. He would say, “You have to know when you have cracked it!”

Darrel Conybeare is the co-director and co-founder of Street Furniture Australia and Conybeare Morrison International. He will join a Q&A at the AILA Fellows Luncheon as part of the 2015 Festival of Landscape Architecture: This Public Life in October.