Kim Ellis is Executive Director of Sydney’s Botanic Gardens and Centennial Parklands, overseeing a network of seven parks from harbourside to mountaintop.

He was Director and CEO of the Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust before the parks joined forces in 2014, and was at the helm throughout the operational integration.

An advocate for green space, Ellis walks one of the seven parks each morning.

Your vision for Australia’s parks and green spaces?

Australia is blessed with some of the world’s best public parks and green spaces, but we should not take them for granted. Around 66% of Australians live in capital cities, and this is increasing over time. Population growth pressures and the changes in lifestyle and demographics are already changing the nature and usage of our public spaces. As park managers we must proactively respond, not reactively.

The one way we can help shape our parks future is to keep the important role of public space in the public eye – to ensure that policymakers, community shapers and urban planners recognise and understand the importance of public space and the need to consider it as critical urban infrastructure.

As an industry we need to share our stories, our successes and our secrets. We need to prove that any investment in green space produces a multiple return on that investment for the community. We need to engage the community and convert them from passive observers to educated advocates. We need to bring kids into nature and let them roam, explore and get to know the world around them.

Let’s ensure green spaces are seen as the connections between, rather than the spaces between. Parks and green spaces can make a real positive difference in people’s lives. We need to not only demonstrate that, but tell the world about it.

What is the importance of parks to families living in cities today?

Incredibly important – and I can say that from both personal and professional experience.

One of the key trends in our city is more people are living in high density housing – homes with no backyard. This lack of private green space makes public green space even more critical.

I recently heard a statistic quoted that the average Australian child spends less time outdoors than a maximum security prisoner. This increased indoor culture is creating a generation of kids losing touch with nature – and creating a sense of disconnection to the real world around them.

Our work is to counter this trend, and provide opportunities for kids and families to get outdoors, connect with nature and create healthier, happier habits.

Public safety is always a priority, so while creating engaging and fun spaces, we always ensure that the environment is a safe and welcoming one. You want families to view visiting the park as something they want to do, not as a chore they feel they should do. And not only visit once, but want to come back again and again.

I recently heard a statistic quoted that the average Australian child spends less time outdoors than a maximum security prisoner.

How did working with Centennial Park as its director and CEO alter your understanding, and maybe appreciation, for parks and public spaces?

With my background in asset management, infrastructure and defence, it’s not surprising that I view strong leadership, sound planning and accountability as the keys to success for any organisation. Never has this been more relevant in the parks and public space industry.

Since starting at Centennial Parklands in 2011 this role has opened my eyes to the challenges and complexity of placemaking and green space management. Over the last five years I see three key learnings to share.

Firstly, public parks and gardens don’t just happen. Behind the façade of a picturesque green space is many hours of meticulous thought and planning. At Centennial Parklands we have been regularly recognised externally, but winning awards is not the focus of our work. Designing, delivering and maintaining a world-class public space that is enjoyed by millions in a sustainable manner is what we aspire to – and what we are delivering.

Secondly, open space is not vacant space. Our public open spaces are often viewed by some as the green places between, something to be filled up over time. They are not. Green space is critical city infrastructure – it improves the liveability of our increasingly urbanised cities. Parks improve the health of our environment, cool our cities, and provide physical and mental health benefits for the community.

Thirdly, to create the best parks and public spaces you really need to surround yourself with the best people – people who have the knowledge, the experience and pride in their work. A visitor can really tell if a place is maintained by people who truly have a personal interest in getting not only the big things right, but also ensuring the little touches are not forgotten.

It is one thing to deliver a new building or create a new environmental habitat, but if the toilets don’t flush or the road is dangerous with potholes, then the visitor comes away with a negative impression. Getting the right people in the right roles was one of my priorities when I first started.

Do you still walk Centennial Park each morning?

Yes, absolutely, however these days it is not just Centennial Parklands. Over the last two years we have undergone a major organisational integration that has seen three botanic gardens and another historic park added to our responsibilities.

So these days I am fortunate enough to be able to take an early morning pre-work walk in one of a number of Sydney’s best green spaces.

These walks are, I believe, critical to the success of my work. Not only do I use them to become familiar with the places I oversee (and maybe drive my asset management team crazy with maintenance requests at times!), but I see firsthand the way in which the community engages and uses these spaces.

Everything we plan, design and deliver is predicated largely on the visitor. If a park or public space is not visitor-friendly, safe and relevant to visitor needs, then it has low utility in the eyes of the wider community, and will not attract funding or support from Government or donors.

I have to say that these morning walks also allow me to meet and engage directly with regular visitors. I am often stopped along the way – sometimes for a friendly chat, sometimes to hear a complaint or a suggestion for an improvement.

Over the years I have learned to enjoy these interactions. The vast majority of visitors love the spaces and want the best for them. They respect the work we do and have the right motivation.

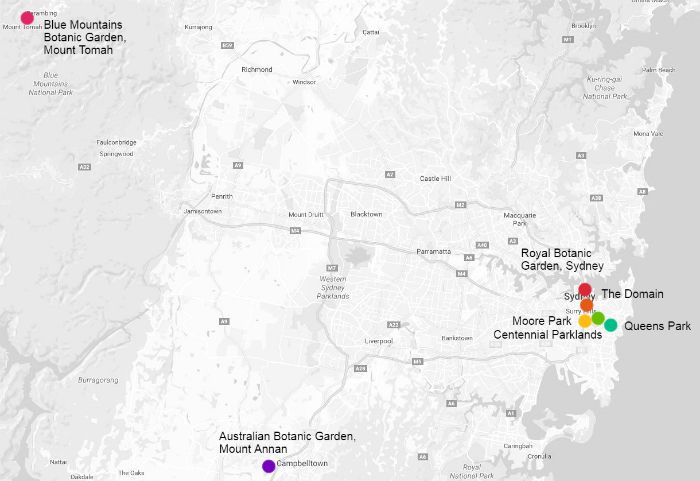

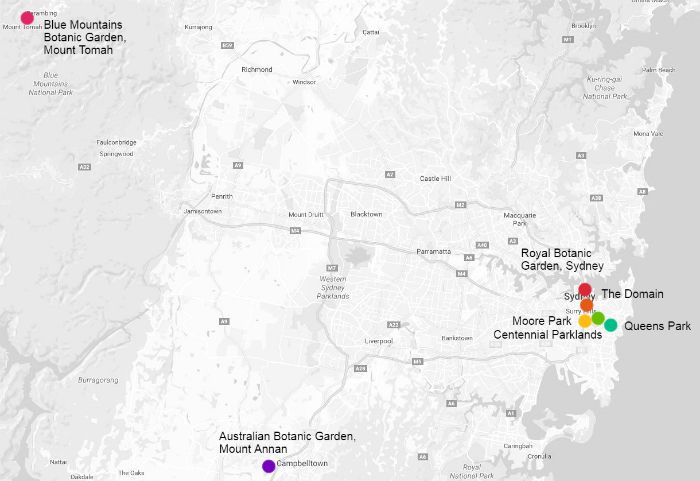

Sydney’s Botanic Gardens and Centennial Parklands, a network of seven green public spaces.

What role do landscape architects play within your team?

A very important role. We have a small in-house team of strategic planners that have ownership of our public design and development projects. My staff ensure the delivery of works is consistent, cost-efficient and timely.

Our model is to buy-in expertise on a project-by-project basis to maximise the use and ideas of some of the best people in the industry.

One of our recent projects was the construction of The Calyx – a new horticultural display centre in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. This was an ambitious bespoke project constructed within the stringent planning constraints of a heritage-listed site and PTW Architects did an outstanding job in developing this world class design.

The role of landscape architects helped ensure the project was delivered on time and on budget through the expertise in placemaking and an understanding of construction in a heritage setting.

Landscape architects are also good at identifying not only the best design options for public space, but also how the visitor will likely engage with the space. This is critical in ensuring design meets user need.

It’s been a couple of years since the operational integration of the seven parks, what results are you seeing?

Any organisational integration is a challenging time for all. Up to 90% of organisational mergers are considered a failure, with clashing organisational cultures and different strategic corporate alignments key reasons for failure.

I can thankfully report that our integration, after two years of hard work, has been one of the great success stories. You may think that merging organisations with a focus on (respectively) parks and botanic gardens may seem straightforward. It was not.

Apart from some staff cultural differences, the challenge was to ensure that the core responsibilities of both organisations were respected and recognised in our strategic planning and resourcing, while at the same time finding efficiencies and operational improvements.

What I identified early on was the transferrable skills and expertise that could benefit all sites. The asset and facility expertise and systems of the Parklands have been brought across to improve the Gardens, while the horticultural and conservation expertise of the Gardens has significantly improved the Parklands.

After a few years of hard work, we are now in a very good place with one united operational team, led by a motivated and empowered Executive team.

The parks and gardens are continually praised as being in the best condition they’ve been in for years. Great planning combined with great people make great places. The future is looking very positive.

The Calyx. Photo: John Gollings

Is the ability to develop masterplans and discussion papers for the parks an outcome of the integration? What value do you see for these long term visions, and for putting ideas out there for public debate?

Master plans and discussion papers have a very important place in making parks and public spaces great. Without such plans, public spaces usually suffer from randomness, irrelevance and lack of accountability. They can also suffer from vested interests taking over or utilising public space for private interests.

Community and government confidence is engendered through having the confidence, understanding and expertise to develop a transparent vision for the future. It is incumbent upon you to plan your future. If you don’t, someone else may step in and plan an alternate future for your site.

Parks and public spaces never stands still. Even if we downed tools and did the minimum amount of maintenance to the Parklands, the Parklands would change.

How? To slightly corrupt a well-known phrase: “no park is an island”. The city around us is changing, and our public spaces are an integrated part of that city. The numbers of visitors and demand for our facilities and services drives change. The demographics and user trends within the community drives change. The climate and urbanisation around us drives change.

It is up to us, as park and public space managers, to plan for and deliver this change, but in a way that respects the nature and importance of your spaces.

I have used the word ‘accountability’ a few times. This is a key reason for developing plans, putting out ideas, and having debates. It is important for visitors and the broader community to not only know what you’re doing, but why you’re doing it. This is part of an engagement strategy that enables us to deliver some of the world’s best public spaces that are loved by millions every year.

Parks and public spaces never stands still. Even if we downed tools and did the minimum amount of maintenance to the Parklands, the Parklands would change.

One of the goals of the integration was to improve areas in the sites that weren’t being particularly well used. Where have you been able to achieve this?

Firstly, just take a look at our visitation and usage statistics. In the last 12 months our three botanic gardens have passed their highest visitation records with an average 20% increase. We have seen 12% year-on-year growth in sport participation in Centennial Parklands over recent years, and our education programs continue to deliver some of the best nature-based programs in Australia.

One project in the last 12 months that really exemplifies this is the new all-weather sports field at Moore Park. Built on the footprint of 10 ageing and underutilised netball courts that were used by around 4,000 people a year, the new all-weather sports field now provides sports facilities enjoyed by over 40,000 a year – with the ability to play a wide range of sports on it.

Vivid debuted at the Botanic Gardens this year, was there a long road to making this happen?

Vivid Sydney coming to the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney was an outstanding success, built on two years of planning and lobbying. Over 21 nights we had more than 500,000 people visit the site, and one of the features – the Cathedral of Light – became the undoubted success story of this year’s entire festival.

While the road from concept to reality was a challenging one, our overriding priority was to create an amazing experience that protected and showcased the Garden environment and heritage. I am pleased to report that after the event, with a little returfing the site was back to its best within a matter of weeks.

What opportunities do you see for the Mount Annan Botanic Garden, being a little farther out of the city centre?

The Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan is also an interesting case study. A 416-hectare site right in the heart of the largest urban growth area in Australia – south-west Sydney. Previously a fenced off garden with an entry fee (and consequently low visitation), the site is now free to enter and draws over three times the visitation.

An important part of this work is to ensure that our sites are not loved to death, so our work in driving increased visitation and use of sites is underpinned by some solid sustainability principles, as well as ensuring we continue to respect the nature of each site.

Our next step at Mt Annan is to develop a land use plan that will guide the development of better access and parking and potential sites for new science facilities.

For you, what is the role of street furniture in the landscape? What marks a good installation?

Critically important to the visitor experience. You can have the most stunning vistas and landscapes for visitors to enjoy, but if the park benches are broken, if the bubblers don’t work, or if the amenities are dirty and uninviting then the overall visitor experience will be severely diminished.

Street furniture should also have a consistent design and purpose to it. Inconsistency is the enemy of the park manager. Aesthetics and functionality make a place look well maintained and well cared for.

We have public element design manuals for our parks and gardens that create a look-and-feel that is contemporary, functional and durable. Our future requirements will include street furniture that integrates with our technology – way finding, interpretation and emergency management.

Street furniture should also have a consistent design and purpose to it. Inconsistency is the enemy of the park manager. Aesthetics and functionality make a place look well maintained and well cared for.

Centennial Parklands encourages mixed-use activities on its paths and fields. Photo: Instagram

View of the Harbour Bridge from the Cathedral of Light in the Royal Botanic Gardens for Sydney’s Vivid 2016. Photo: Destination NSW.

The Australian Botanic Garden at Mount Annan includes around 2,000 species of native plants.

In Profile is a Q&A series featuring Australian influencers of the public realm.

Interviewees are players in the public sphere with compelling stories, not always landscape architects or affiliated with SFA.

To nominate a subject, please contact the editor via editor@streetfurniture.com